![]()

|

To treat or not to treat…

The first decision and sometimes the most difficult decision to make is which epilepsy patient to treat. Only a minority of patients who have a single seizure will go on to develop multiple seizures, therefore it is not necessary for every patient with a single seizure to be treated.

Neurologists use several factors to determine which patients should be on seizure therapy including:

- Results of the EEG (brain wave test)

- MRI of the brain

- Circumstances surrounding the first seizure or two.

In addition, the feelings and concerns of the patient need to be taken into account since any treatment plan the patient is not in complete agreement with is doomed to failure.

Which medication is the right one for me?

Once it is decided that the benefits of treatment outweigh the risks, it is important to choose an appropriate treatment with the least side effects, as many patients will have to take the medications for several years.

The principal benefit of the newer anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) are fewer side effects. They have not shown any increase in single agent epilepsy control or efficacy. In fact, in all head-to-head studies that Dr. Loftus is aware of, no single epileptic agent has been shown to be superior to any other agent if prescribed for the proper type of seizure and also provided the medication can be tolerated by the patient.

The principal differences in the of anti-epileptic drugs are:

- Medication side effects

- Frequency of administration

- Method of administration

- Cost

There are many factors that the physician and patient must consider before deciding on medication. For example, some of the medications such as Neurontin and Depakote cause weight gain and should therefore be avoided in patients who are overweight. Topamax, Zonegran, and Felbatol cause weight loss and are therefore more likely to be used in those who are overweight. AEDs such as Lamictal, Keppra, and Neurontin do not interfere with birth control pills. Individualized treatment is key and therefore it important for the patient to choose a physician who is comfortable with all of the newer medications.

Of the newer AEDs, Guidelines of the American Academy of Neurology support initial treatment of partial onset seizures with Neurontin, Lamictal, Topamax, and Trileptal. For newly diagnosed absence seizures, only Lamictal is supported among the new AEDs for initial use.

Two of the older anti-epileptics, phenobarbital and primidone, should not, in Dr. Loftus’ opinion, be used for controlling seizures in adults. These medications are very sedating and over time, they are metabolized by the body more slowly therefore the levels slowly rise in the patient. Many of the patients taking them have not even realized the degree they were being negatively impacted by the medication until it was discontinued.

The use of the vagal nerve stimulator (VNS) has been a breakthrough in the treatment of epilepsy. Just like medication, the VNS has side effects, but the side effects are very different from the other medications and therefore it is excellent to use in combination with other AEDs. In addition, medication compliance, which is difficult with a chronic disease like epilepsy, is guaranteed (at least until the battery runs out).

In a study by Kwan and Brodie published in the New England Journal of Medicine during 2000, the very first seizure agent they were able to tolerate made approximately 50% of patients seizure-free. Only 13% became seizure free after switching to the second agent that they could tolerate. After a second agent, all subsequent medication trials (some in combination) resulted in seizure freedom in only an additional 4% of the time. Therefore, it should be possible to completely control seizures medically in about 2/3rds of all patients. Conversely, once a patient has failed to have their seizures controlled by 3 agents they were able to tolerate, non-medical therapies like epilepsy surgery needs to be considered. A detailed discussion of epilepsy surgery is beyond the scope of this web site but patients with temporal lobe epilepsy associated with mesial temporal sclerosis who are medically intractable do best with surgery.

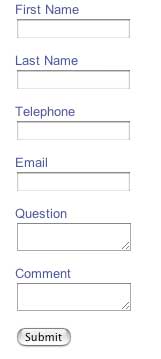

As part of an effort to bring the best possible practice of epilepsy treatment to the most patients possible, Dr. Loftus has developed an online anti-epileptic adverse event profile which the patient can bring to their physician to show if they are having an adverse reaction to their current regimen.

Can I ever stop taking my epilepsy medication?

Because there is no "best" medication, the neurologist and patient must work together as a team in choosing, discontinuing, and switching the patient's medication.Once on anti-epileptic therapy, deciding when to stop therapy can be an even more difficult decision. In general, most neurologists wait two or three years (Dr. Loftus waits three) for a patient to remain seizure-free and aura-free before considering this decision. Again, the neurologist will look to the MRI, EEG, and most importantly, the patient's history and feelings on the subject before making a decision.